Key Takeaways

- Students have increasingly complicated academic and mental-health needs, teachers say. When you put 33 or 38 or 40 of them in one classroom, it's impossible to meet their individual needs.

- Meanwhile, the national teacher shortage means educators are frequently giving up their planning time to cover additional classes. They're overworked and exhausted.

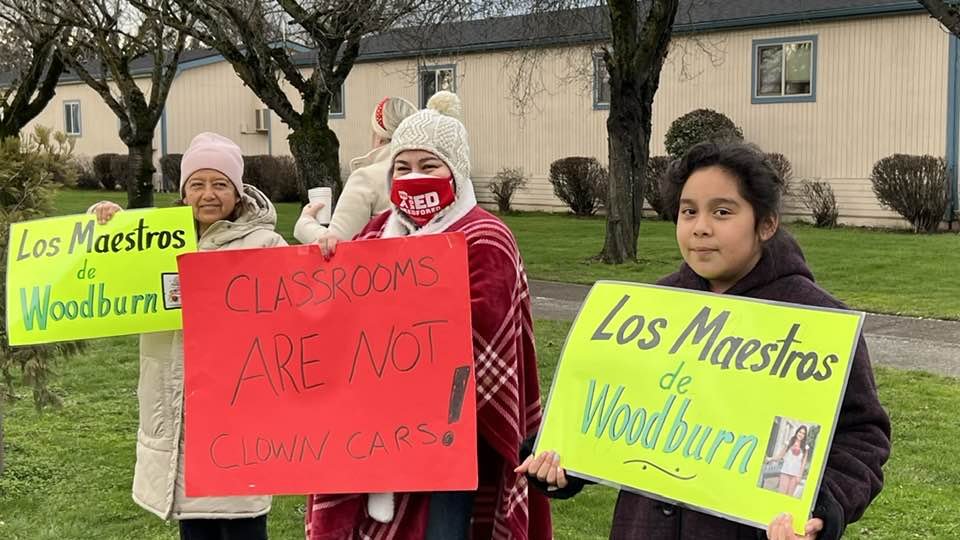

- The issue has become an increasingly hot topic at the bargaining table and fueled two near-strikes in Oregon this spring, where union members won special-ed caseload caps and immediate, guaranteed help for teachers with big classes.

A few years ago, Kathia Ruiz had a whopping 29 students in her fourth-grade classroom. This year, through some lucky twist of fate, the Woodburn, Oregon, teacher started the year with just 18.

“It was amazing all the things I could do! The differentiation that was possible,” she says. The difference between nearly 30 students and less than 20 was huge. To her, the benefits of smaller class sizes were clear.

But when Ruiz and other members of the Woodburn Education Association bargaining team sat down with district administrators, the district didn’t—or wouldn’t—see it. Their lack of consideration was “mind blowing to me,” she says. “[Class size] has such an impact on what teachers can do. We want to help and support every student— but there’s only one of us and only so much we can do with a big class.”

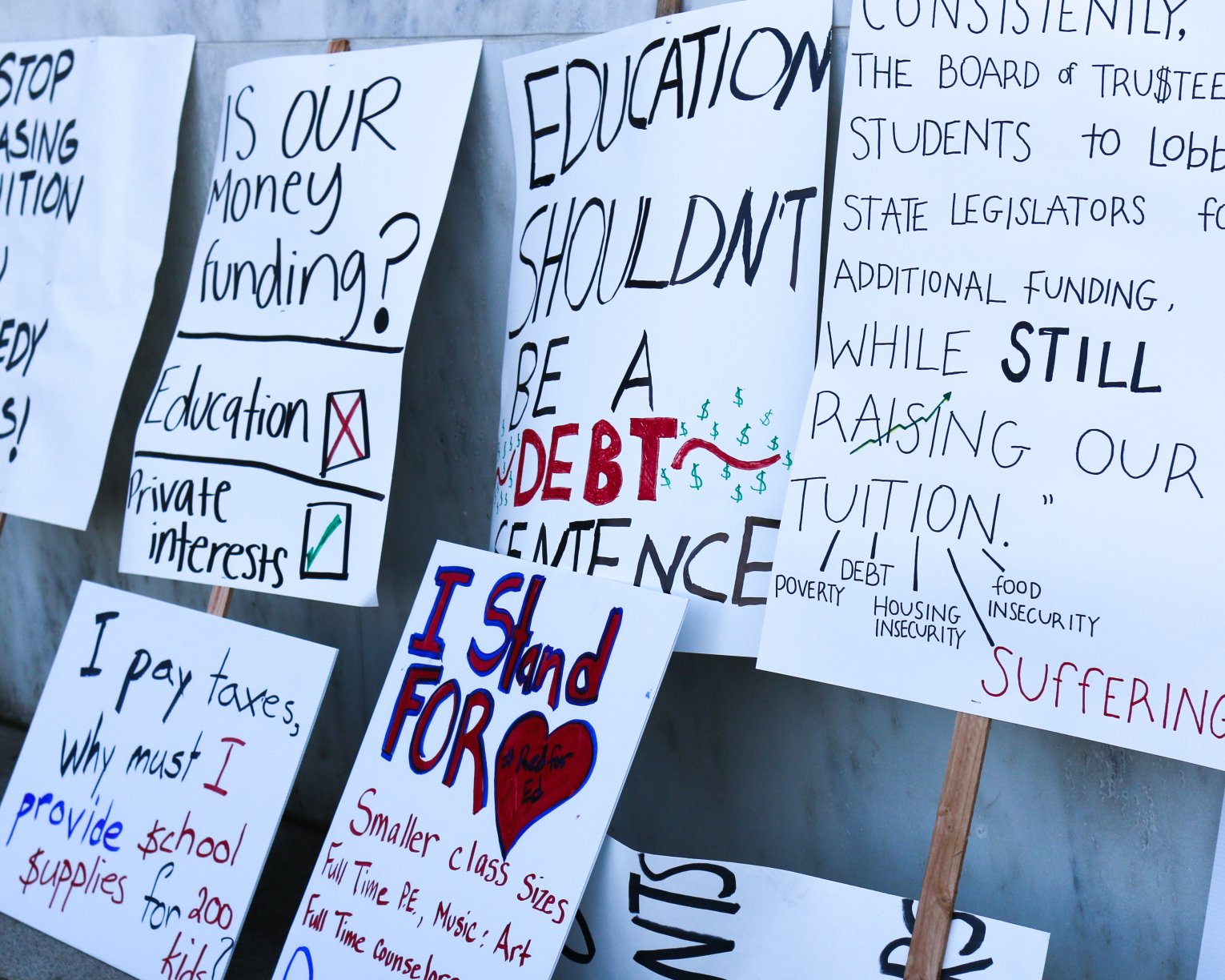

Across the nation, educators agree. In Columbus, Ohio, in the fall of 2022, teachers went on strike to get lower class sizes. A month later, Malden and Haverhill, Mass., educators did the same. This spring, in both Woodburn and 20 minutes away in Silverton, Ore., union members went to the brink of striking. Whether it’s at the bargaining table, in the halls of state Capitols, or in places where educators and parents confer about things that matter, class size is a hot topic.

“We haven’t seen this historically—until this year. This year, in almost every strike and near-strike, starting with Columbus, class size has been a big issue. It’s more prominent and more significant,” notes NEA’s Andy Jewell, a senior collective bargaining specialist who has tracked educator strikes for several decades.

Whether the significant interest is because class sizes have increased, as a side effect of the national teacher shortage, or because students’ individual needs have grown overwhelming since the pandemic isn’t clear. What is certain is that educators—and parents—agree smaller classes and special-ed caseloads would help educators and students succeed.

“Teachers have to demand what they know is best for the students in their room. Nobody else is coming to save us,” says Alison Stolfus, president of the Silver Falls Education Association in Silverton. “You have to get organized and demand it!”

What Students Need: Attention

Educators believe class size matters. Common sense—and a lot of research— confirms they’re right.

The most famous study is the Tennessee one, authorized by the Tennessee legislature almost 40 years ago. Called Project STAR (for Student-Teacher Achievement Ratio) and run by a Harvard professor named Frederick Mosteller, the project compared 6,500 K-3 students, half in classes with just 13-17 students and half in classes of 22-25. Mosteller found that the students in the smaller classes did significantly better on academic tests—and that the difference persisted for years. It was compelling evidence.

“People talk about ‘silver bullets’ in education, but the only thing that we know works is small class size,” says Misha Pfliger, a social studies teacher at Woodburn’s alternative high school where classes can be half the size of the regular high school’s. When students tell Pfliger, “Wow, I’ve never done well in school before,” he responds: “You’ve never had the opportunity! You didn’t get the attention you need to succeed.”

It's just common sense, say educators. When a speech-language pathologist has a caseload of 100 students, as they have in Woodburn, Ore., says union president Kathy Kuftin, each student ends up with maybe 5 minutes a week of practice, twice a week. “When caseloads are smaller, we can give better service to students,” says Kuftin.

While nine of 10 teachers say smaller class sizes would help students, they also would help teachers. Today's educators are exhausted. A study last year found that they work 54 hours a week, on average, for little pay. Mental-health issues are skyrocketing—and not just among students. Staff are resigning to preserve their own mental health.

Immediate, Guaranteed Help

In Silver Falls and Woodburn, bargaining team members didn’t want to settle for new contract language that simply provides more money to teachers with big classes. In places with those types of bonuses, districts rarely, if ever, make classes smaller. It’s a lot cheaper to pay a small bonus than invest in additional teachers or classroom aides.

“What we got, in the end, was guaranteed help for students,” says Emily Rao, a Silver Falls social studies teacher and bargaining team member. “Once you get to a specific number, you get specific help.”

In Woodburn, the new contract focuses on K-3 class sizes. In Silver Falls, it’s K-12. In both places, when a class hits a specific number of students, the district is mandated to implement one of several possible supports. These include adding a classroom aide; hiring an additional teacher; transferring students; blending classes; and providing additional time for planning and grading.

“The district’s lack of interest in class size didn’t make any sense to us, and they didn’t have any rationale for it,” says Stolfus. “It felt like common sense to us, but resistance to having it in the contract [by management] was extreme. We were told we were hurting our principals’ feelings!”

In addition to getting help with class sizes, Silver Falls and Woodburn educators also won much-needed salary raises and Woodburn educators bargained to protect the district’s prized dual-language program.

"Staff is Breaking. Students are Breaking."

In 2021-2022, 25 percent of Woodburn teachers left, many of them midway through the school year. “You didn’t used to see resignations in November, February... It’s a new thing and it’s really disheartening to see it happen,” says Ruiz.

The job feels more difficult than ever, union leaders say. Shortages of educators means teachers are regularly giving up their planning time to help out, says Tim Martin, president of the Kent Education Association in Washington. They’re overworked and exhausted. Meanwhile, students’ needs have skyrocketed.

“It’s been a very, very difficult year,” says Martin. In fact, this year more Kent teachers have gone out on medical leave than ever before. “People are breaking. Students are breaking. Staff is breaking.”

Instead of hiring more teachers, Kent district officials ask teachers to take more students or teach additional classes. “I went into one classroom—a high school chemistry class—and my jaw dropped on the floor. There were kids with clipboards for desks, kids sitting on counters and heaters and the floor. I had no idea how she was going to be able to do labs!” he recounts.

“Kids are like, ‘Why am I here? I can’t get one-on-one time. I can’t get help.’ So, they act out,” he says.

This year, the Kent union will be back to the bargaining table, Martin says. The two big issues? Mental-health supports for students and staff and working conditions, which includes class size and caseload caps. “I’m optimistic we will get there,” says Martin, “but it’s not going to be an easy path.”

Speak Up!

In Minnesota, union members will soon have similar conversations at the bargaining table. This month, thanks to Education Minnesota members, Gov. Tim Walz signed into law a massive bill that, in addition to delivering an additional $5.5 billion for pre-K-12 education, makes staffing ratios a mandatory subject of bargaining.

Subsequently, a reporter asked Education Minnesota President Denise Specht, “Will Minnesota schools finally lower class size?” In a recent editorial, she answered: Possibly, yes. “Educators have our priorities, but there are few guaranteed outcomes,” she wrote.

Local unions may prioritize class-size reductions at the bargaining table. They may or may not succeed. “Educators working in unions will use the collective bargaining process to influence how the money is spent and put a priority on expenditures that directly affect the classroom, but that may not be enough,” Specht wrote. “The families of students and members of the community who support their local schools should stay engaged… Speak up for the programs, buildings and staff you support.”

In Edina, Minn., a suburb of Minneapolis, class sizes aren’t too high overall, says Jason Dockter, president of the Education Minnesota-Edina union. “Our ratios haven’t increased in 10 years. We have a district that understands how low class-sizes benefit student achievement,” he says. But every year, there are still a few uncommon outliers—classes that that exceed enrollment expectations—and “when a teacher finds themself with a class of 29, it’s a big issue for them.”

“I see the law as a great opportunity,” says Dockter. “We’ve always viewed class size and staffing ratios as an aspect of working conditions, and our members want a say in their working conditions.”

Learn More

Do More

Active anywhere decisions impact our students.

From the School Board to the Statehouse or even the White House, OEA members make our collective voice heard on a host of issues that impact our students, educators, and communities.

Learn more about what we're doing to improve the lives of our students, educators, and families.